INTRODUCTION

Through the SONQO-CALCHAQUÍ Program (Edi- tions I to III), a group of physicians from different parts of the country conducted cardiovascular checks on the inhabitants of the indigenous communities of the Calchaquí Valleys (provinces of Tucumán, Salta, and Catamarca) who live in midand high-mountain areas. The population presented a high rate of obesity, a prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors similar to that of urban centers, and a diet based on flour. These results show an adoption of cultural, economic, and/ or social elements typical of Western culture, either voluntarily or imposed, in their lifestyles. (1,2,3) This westernization has already been described in other indigenous populations in Argentina. (4,5,6)

The adaptive challenges of performing activities (7) and living (8) at altitudes above 2500 m above sea level (high-mountain) are still being studied worldwide. In Argentina, high-mountain indigenous communities have been scarcely studied due to a combination of characteristics that include difficult access, an isolated environment, and their closed nature. However, a westernization of their nutritional habits is being observed, especially in younger populations. 9 In the IV Edition of the SONQO-CALCHAQUÍ Program, the cardiovascular health study was extended to the residents of the Coranzulí community (Susques department, province of Jujuy).

The Coranzulí community is located 4100 meters above sea level in a rugged and dry environment. 10 The population of the Susques department in 2022 was 4098 inhabitants, 11 and that of Coranzulí in 2014, 339 inhabitants. 10 There is no more recent data, and the actual number of inhabitants in Coranzulí is difficult to estimate because most of them are semi-nomadic and have been herding American camelids since pre-Hispanic times. 10 This population presents itself as a closed and isolated indigenous community. However, the advance of the mining industry in the area poses multiple challenges that must be evaluated. 12

The objective of this study was to characterize the cardiovascular health status of the indigenous population of Coranzulí.

METHODS

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study. Residents (aged 18 years or older) who voluntarily attended the IV Edition of the SONQO-CALCHAQUÍ Program (September 30 to October 4, 2024) were evaluated. In order to assess only the indigenous population, we worked in conjunction with the community delegate. Seven clinics were set up at Secondary School No. 18 (Coranzulí), where the following tests were carried out:

Clinic 1 (Laboratory): routine tests were performed. Glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the MDRD-4 formula. 13 Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and serology for Chagas disease were also measured.

Clinic 2 (Surveys):

-

Targeted socioeconomic survey. 1

-

24-hour dietary recall test. 14

-

Food consumption frequency test: semi-quantitative questionnaire indicating the frequency of consumption of 19 foods (daily, weekly, or monthly) in the last year. (2,3)

-

SF-12 questionnaire: assesses self-perceived health status, with a score between 0 (none) and 48 (maximum). 15

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. 16

Clinic 3 (Anthropometry, blood pressure, and oximetry): body mass index (BMI) was calculated, and, expressed in kg/m2. Values ≥18.5 and <25 were considered normal. Waist circumference (normal ≤ 88 cm in women and ≤ 102 cm in men) and neck circumference (normal ≤43 cm) were measured.

Blood pressure (BP) was assessed with a digital sphygmomanometer (Omrom® 7120) according to the guidelines of the Argentine Consensus on Hypertension. 17

Oxygen saturation (%) and heart rate (bpm) were measured with a digital oximeter (Contec® CMS50N).

Clinic 4 (Electrocardiogram, ECG): a 12-lead digital recording (Jotatec® TaurusTouch) was performed.

Clinic 5 (Echocardiography): recording of cardiac structure dimensions (mm) and areas (cm²) (Esaote® MyLab 30 Gold) were made, with calculation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) using the Simpson biplane method. 18

Clinic 6 (Peripheral arterial ultrasound): Doppler ultrasound technique was used on neck and iliofemoral arteries (Esaote® MyLab 30 Gold).

Clinic 7 (Physical capacity): exercise tolerance using the Ruffier-Dickson test. 19 The Ruffier index [(sum of baseline, intra-exercise, and post-exercise heart rates) - 200)/10] was calculated and the following scale was used: 0: very good; 0.1 to 5: good; 5.1 to 10: average; 10.1 to 15: insufficient; and 15.1 to 20: poor.

Maximum handgrip strength was measured using a hydraulic dynamometer (Jamar®) in the dominant hand, calculated as the average of three attempts. Values ≥ 27 kg in men and ≥ 16 kg in women were considered normal. 20

Exclusion criteria included sensory, cognitive, or motor disabilities.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as frequency and percentage for qualitative variables and as mean ± standard error for quantitative variables. Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate, and quantitative variables using Student's t-test. Data were analyzed using Prism 5.0.2 software. Values with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Provincial Health Ethics and Research Committee of the Ministry of Health of the Province of Jujuy (File No. 773-1251/2024). All participants gave their informed consent to participate.

RESULTS

A total of 404 persons were analyzed in the IV Edition of the SONQO-CALCHAQUÍ Program. Among them, 241 (average age 44.1±0.1 years) were included in this study: 139 women (57.7%) and 102 men (42.3%). All the communities where residents came from were located more than 2500 meters above sea level.

Clinic 1: Table 1 shows the results of the routine analysis. The calculated glomerular filtration rate was 107.4±1.7 mL/min, and TSH values were 5.8±1.8 mIU/L. Only one resident tested positive for Chagas disease serology.

Clinic 2:

Targeted socioeconomic survey:

Educational level: 5.0% were illiterate; 56.4% had completed primary school; 21.6% had completed secondary school; and 17.0% had completed tertiary educa tion.

Occupation: 60.2% were active workers; 19.9% performed household tasks; 0.8% were students; 12.9% were retired; and 6.2% were unemployed.

Health coverage: 71.4% had social security; 0.8% had prepaid coverage, and 27.8% had no health coverage.

In 91.7% of cases, residents had a cell phone, with an average use of 3.9±0.2 hours/day.

Regarding cardiovascular risk factors, 13.7% had history of hypertension (HTN); 2.9% had diabetes, 16.2% had dyslipidemia, and 15.8% were smokers. The age of the residents was higher in the group with HTN (54.2±2.6 years vs. 42.4±1.0 years in those without HTN; p<0.001) or diabetes (57.0±3.3 years vs. 43.7±1.0 years in residents without diabetes; p= 0.032).

24-hour dietary recall test: breakfast consisted mainly of tea (43.2%) and mate (30.3%), usually accompanied by bread (40.2%). At mid-morning, 36.1% had a snack. At lunch, 78.4% ate meat (beef 58.9%, chicken 14.5%, and llama 5%), usually accompanied by flour or rice. Dessert was fruit (39.8%), cornmeal ("anchi"; 9.1%), or another dessert (7.5%). The afternoon snack was similar to breakfast, and dinner was similar to lunch.

Table 1

Routine test results (n=241)

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Hematocrit (%) | 54.4±0.4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 18.1±0.1 |

| Red blood cells (million/dL) | 6.2±0.0 |

| White blood cells (thousand/dL) | 6.8±0.1 |

| Platelets (thousand/dL) | 245.2±3.6 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm) | 7.5±0.3 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 76.6±0.7 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7±0.0 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 20.6±0.4 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 7.2±0.2 |

| GPT (IU/L) | 6.9±0.2 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 190.4±3.8 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) Total | 0.4±0.0 |

| Indirect | 0.3±0.0 |

| Direct | 0.2±0.0 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) Total | 169.1±2.8 |

| HDL-C | 42.8±0.4 |

| LDL-C | 101.5±2.7 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 122.0±2.0 |

GOT: Glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase; GPT: Glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Variables are presented as mean ± standard error.

Food consumption frequency test: during the previous year, residents consumed the following number of monthly portions: lean meat: 21.5±1.3 (mainly llama and lamb); white meat: 10.0±0.1; fish: 1.8±0.4; vegetables: 37.1±1.5; fruit: 28.0±1.6; nuts: 1.8±0.5, legumes: 3.8±0.5; fat: 22.8±1.3; refined cereals:

22.8±1.8; whole grains: 1.6±0.8; sugar: 17.6±1.6;

dairy products: 9.2±0.7; and eggs: 11.9±0.9.

Almost half of the residents (48.9%) reported regular alcohol consumption.

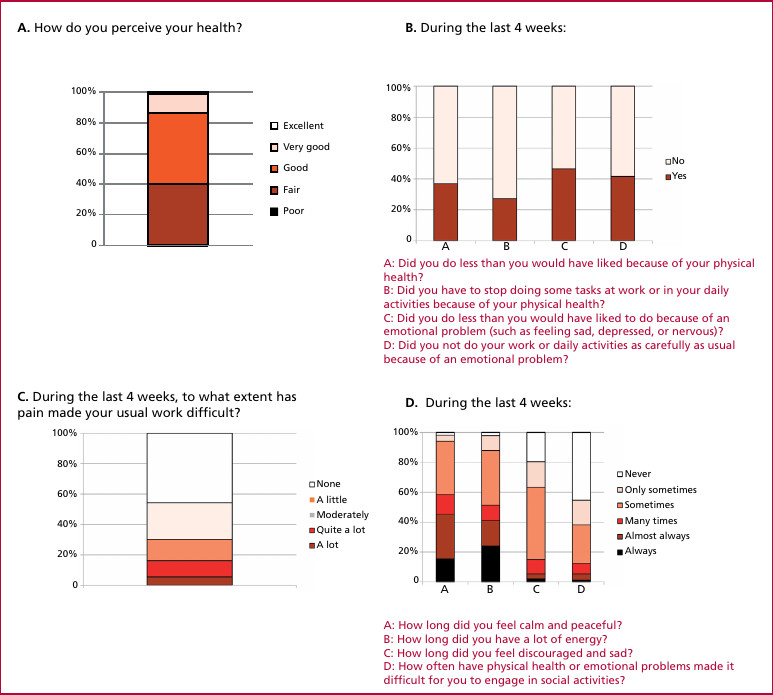

SF-12 questionnaire: the average score was

26.7±0.3 points (63.7±0.6% of the total value). Figure 1 shows the answers to the questionnaire.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: bedtime was at 10:42 p.m.±00:05 a.m. and wake-up time was at 7:48 a.m.±00:02 a.m. (9.1±0.05 hours of sleep). During the last month, 38.8% of residents had no trouble falling asleep; 51.7% got up during the night to go to the bathroom; 16.3% reported feeling apnea; 38.3% snored;

and 30.4% had nightmares. Regarding sleep quality, 29.9% indicated that it was very good; 59.7% fairly good; 7.5% fairly poor; and 2.8% very poor; 96.7% did not take sleep medication.

Clinic 3: Table 2 shows the results of the parameters recorded. According to BMI, 0.4% were malnourished; 32.0% had normal weight; 36.5% were overweight; 23.2% were obese; and 7.9% were morbidly obese. Waist circumference was elevated in 56.7% and neck circumference in 8.0% of residents. Systolic BP was elevated in 8.8% of the population and diastolic BP in 12.6%. Average arterial O2 saturation was 88.3 ± 0.4%.

Table 2

Anthropometric and hemodynamic variables of the population (n=241)

| Variable (Unit) | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric variables | Weight (kg) | 69.5±0.9 | |

| Height (cm) | 158.4±0.5 | ||

| BMI | 27.8±0.3 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 96.2±0.8 | ||

| Neck circumference (cm) | 37.4±0.3 | ||

| Arm span (cm) | 149.1±2.7 | ||

| Upper arm | Right | 28.8±0.3 | |

| circumference (cm) | Left | 29.1±1.1 | |

| Calf circumference | Right | 35.2±0.2 | |

| (cm) | Left | 35.2±0.2 | |

| Hemodynamic variables | Blood pressure (mmHg) | Systolic | 115.2±1.0 |

| Diastolic | 75.9±0.7 | ||

| Differential | 39.5±0.8 | ||

| Mean | 88.9±0.7 | ||

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 88.3±0.4 | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 69.8±0.7 |

BMI: body mass index; bpm: beats per minute. Variables are presented as mean ± standard error

Clinic 4: Mean heart rate on the ECG was 68.8±0.7. The average QRS complex duration was 101.7±7.4 msec., and the QT interval 404.9±2.1 msec. The cardiac axis was 43.6±4.5°. In 32 residents (13.3%), the axis was deviated to the right, and 17 (7.1%) had right bundle branch block. One resident had atrial fibrillation.

Clinic 5: Table 3 shows the quantifiable findings of the echocardiogram. Thirteen residents had mitral regurgitation; 6 had tricuspid regurgitation; 3 had aortic stenosis; and 1 had pulmonary stenosis. Hypokinesia was found in 7 residents and abnormal septal motility in 1. In 5 residents, the right ventricle was dilated. Signs of pulmonary hypertension were found in 7 residents.

Table 3

Quantifiable echocardiographic findings. Measurements in the parasternal long axis. (n=241)

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| LVEDD (mm) | 41.7±0.5 |

| LVESD (mm) | 25.8±0.3 |

| LVEF (%) | 63.6±0.5 |

| IVS thickness (mm) | 9.5±0.2 |

| PWT (mm) | 9.5±0.4 |

| LVOTd (mm) | 18.5±0.2 |

| Ao root(mm) | 22.0±0.3 |

| LAAPD (mm) | 16.7±0.3 |

Ao root: aortic root diameter; IVS: interventricular septum; LAAP:Left atrial anteroposterior diameter; LVEDD: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD: left ventricular end-systolic diameter; LVOTd: left ventricular outflow tract diameter; PWT: posterior wall thickness

Variables are presented as mean ± standard error.

Clinic 6: No aneurysms, tumors, or malformations were found in any resident.

Neck arteries: Seven residents had myointimal thickening. Ten residents had thyroid nodules. There was no difference in TSH values between residents with and without nodules.

Iliofemoral arteries: Three residents had myointimal thickening and five had wall irregularities.

Presence of plaques: 23 residents had atheromatous plaques in the carotid bed; 8 in the iliofemoral bed and 2 in both beds. Ninety percent of residents had no plaques in any of the beds studied.

Residents with atheromatous plaques were older (56.1±2.7 years vs. 42.2±1.0 years in those without plaques, p<0.001).

Clinic 7:

Ruffier-Dickson test: Baseline HR was 70.7±0.8 beats/min; during exercise 96.0±1.3 beats/min (24.7±1.0% increase from baseline), and after exercise 72.6±1.0 beats/min (23.3±0.9% decrease from exercise). The Ruffier index was 4.1±0.3. It was considered very good in 15.6% of the population; good in 50.5%; average in 28.0%; insufficient in 4.1%; and poor in 1.8%.

Grip strength: The average value was 29.4±0.6 kg.

In 80.3% of cases, it was within the normal range.

DISCUSSION

The population studied has an above-average selfperception of their health, 15 with good sleep quality and good cardiovascular function accompanied by adaptive changes to life at high altitude. On the other hand, a high prevalence of overweight/obesity with in creased waist circumference was found. Added to this is high alcohol consumption.

The population was younger than that studied in previous editions of the SONQO- CALCHAQUÍ Program. (1,2,3) It should be clarified that this Program includes residents who attend voluntarily, which introduces a bias, since older residents have greater difficulty participating, thus selecting a younger population.

Unlike other editions of the SONQO-CALCHAQUÍ Program, O2 saturation values were below 90%. These values, which in other situations would be ground for hospitalization, 21 have been described as "normal" in high-altitude populations. 22 Increased hematimetric values, also described in other high-altitude populations, 23 would be compensatory to hypoxia. Although the hemodynamic cost of this adaptive process is still unclear, the fact that the echocardiogram and physical capacity were within normal limits indicates a cardiovascular physiology compensated for these conditions. This hypothesis is supported by the results of the Pittsburgh Index, with good sleep quality and low prevalence of apnea, as sleep quality has been shown to be altered by hypoxemia. 24 In addition, they presented an electrocardiographic tracing within normal limits, a fact already observed in other high-altitude populations, 25 and laboratory indices of renal and hepatic function within physiological ranges.

Elevated TSH values were found, and in some residents, thyroid nodules. Alterations in the hypothalamic-thyroid axis have been described in high-mountain populations 26 so the real role of these findings in cardiovascular function, and whether a diet supplemented with iodine could be beneficial, should be evaluated in future studies.

With regard to the nutritional status, 67.6% of the population had an increased BMI (with 7.9% reaching morbid obesity) and 56.7% had increased waist circumference. These findings are similar to those observed in previous editions of the SONQO-CALCHAQUÍ Program in other indigenous populations in northwestern Argentina (1,2,3) and to those reported in other American indigenous communities. (27,28) Obesity, currently considered a pandemic, 29 is also affecting indigenous populations. (1,2,3, 27,28,3,31)

On the other hand, the Coranzulí population has a low prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, and cholesterol and blood glucose levels within the normal range. These cardioprotective characteristics could explain the low prevalence of atheromatous plaques in the arteries studied, a phenotype shared with the indigenous populations of the Calchaquí valleys. (2,3) This cardioprotective phenotype is more evident in younger residents (who have a lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerotic plaques). Although the genetic and/or epigenetic factors involved remain to be elucidated, the nutritional regime could play a role in this regard, as the diet preserves indigenous elements (e.g., mate, llama meat, and "anchi"). Added to this is the physical activity that residents perform in daily tasks, which is reflected in their physical capacity. Further studies with similar populations may shed more light on this aspect. Another factor to study, which could have some implications, is the low daily use of cell phones. Excessive use has been shown to increase cardiovascular risk. 32

The beneficial and harmful effects of westernization on the cardiovascular health of indigenous peoples are still being debated. Although associated with higher obesity rates, it also promotes access to resources and technology linked to longer life expectancy. 33 In Coranzulí, this ambivalence is exemplified by two facts: on the one hand, a high prevalence of overweight/obesity (already described in other indigenous communities) accompanied by high alcohol consumption, but on the other hand, a high rate of medical coverage and a low illiteracy rate.

CONCLUSIONS

The Coranzulí community presents itself as an indigenous population adapted to highmountain life, which maintains indigenous elements with cardioprotective characteristics, notably nutritional habits and sleep quality. However, it is undergoing a westernization process. The task remains to evaluate the true role of these changes (including the massive influx of the Internet worldwide) on the general and cardiovascular health of this population, for which it is necessary to continue multisectoral studies, such as the SONQO- CALCHAQUÍ Program.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following entities, without whose contribution this study would have been impossible. In alphabetical order:

-

Argentine Society of Cardiology, represented by its President, Dr. Pablo Guillermo Stutzbach

-

Government of the Province of Jujuy

-

Coranzulí Secondary School No. 18

-

Emergency Medical Assistance System of Jujuy

-

La Chata Solidaria NGO

-

Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Jujuy

-

Ministry of Education of Jujuy

-

Ministry of Health of Jujuy

-

Municipal Commission of Coranzulí

-

School of Medicine of Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, represented by its Dean, Dr. Demetrio Mateo Martínez

Limitations

The study population was small and in advanced stages of the disease.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

(See authors' conflict of interests forms on the web).